The Ocean Going Farmer by Nick Halmos

Nick currently resides in Santa Cruz, California where he runs City Blooms and works to make quality, sustainably grown food accessible to an expanding population.

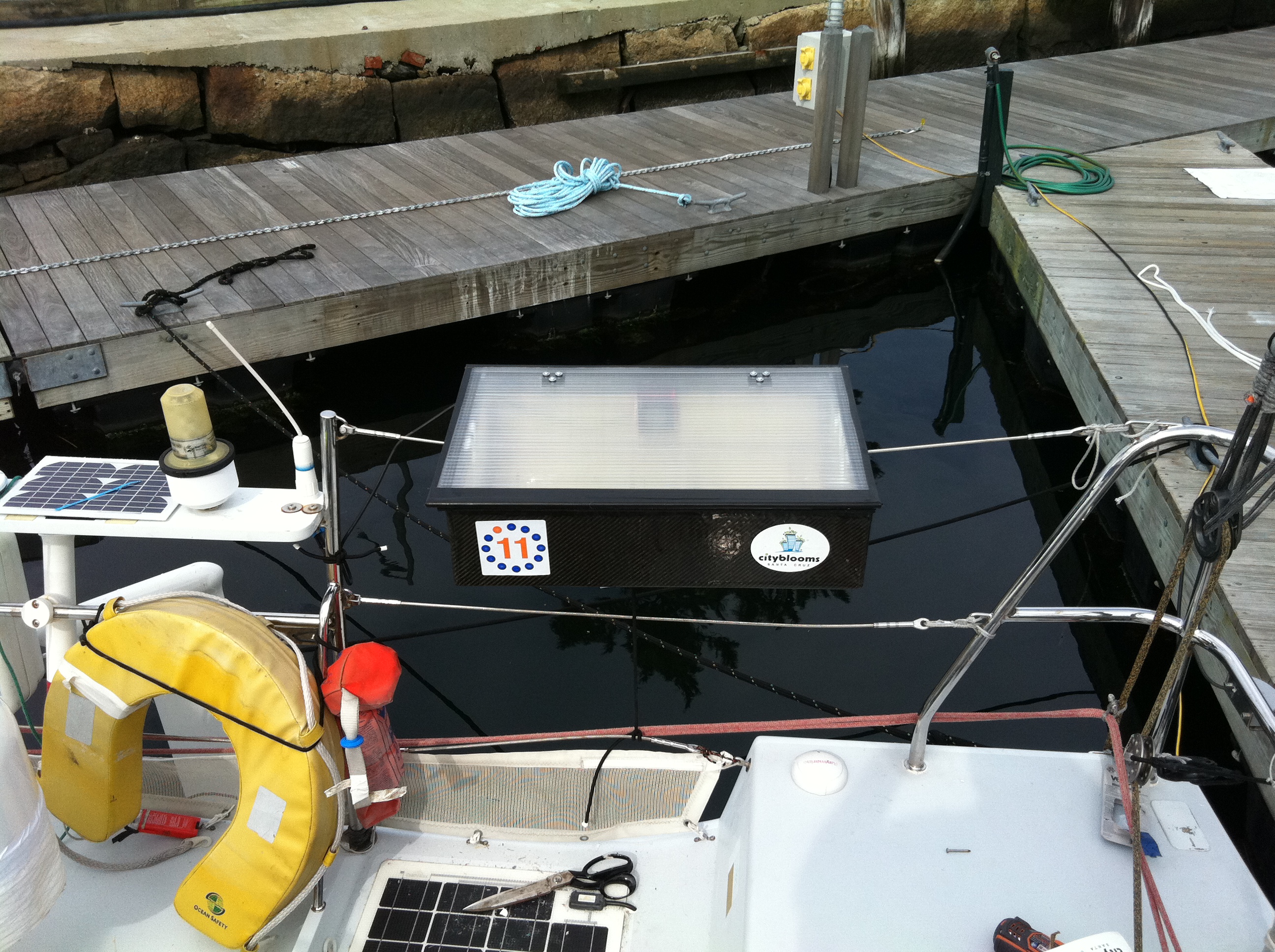

In the fall of 2011, my fellow 11th Hour Racing teammate, Hugh Piggin and I departed from France aboard a Class 40 as competitors in the Transat Jaques Vabre. Over the course of 26 days at sea, we laid a 6000 mile track across the Atlantic that exited the English Channel, wound south through the Azores, across the Atlantic to Puerto Rico, and a final 1000 mile sprint to Costa Rica. One of the things that set 11th Hour Racing’s entry apart is that our boat, the mighty Cutlass, carried the world’s first carbon fiber oceanic hydroponic system. This first iteration of the Cityblooms Aquatic Project was an effort to grow edible and nutritious produce in the harsh and unforgiving environment that is a shorthanded race boat.

The idea was quite elegant in its simplicity. Thanks to the incredible minds of Bernoulli and Newton, we know that pressure differentials are created as air flows across the surface of an airfoil, which can propel a boat through water without the use of hydro-carbons (Hoooray!!!). As the vessel moves forward, water passing under the boat can turn the propeller of a hydro-generator. The resulting clean energy can power a desalinator to create fresh water. Take the water, add some seeds, wait 12 days, eat, and repeat from the beginning.

The point of this somewhat whimsical exercise was twofold.

- First, to demonstrate that food production can be made so lightweight that we would place the equipment on a race boat. This attribute has broad implications to the field of rooftop urban agriculture

- Second, to demonstrate that the technology currently exists to conduct sustainable agricultural operations in a place as inhospitable to terrestrial flora as the mid-Atlantic

The task of maintaining stocks of fresh produce on oceangoing vessels has plagued sailors for centuries. Until a few decades ago, the thought of fresh produce beyond the second or third day at sea was optimistic. 25 years of advancement in refrigeration has helped the situation, but only modestly. Quality fresh produce remains fantasy in most ports of call around the world, even if you can manage to keep it cold for a few days. The practices we sought to develop could be put to use to improve crew nutrition and environmental impact on any vessel that regularly puts to sea for more than a few days.

As with most things in life, a relatively simple theory presents complications when reduced to practice. Fortunately, the challenges encountered in our first attempts at oceanic farming are not insurmountable. What follows is a brief explanation about how we approached the problem, while incorporating some lessons we learned in the hopes that others will improve these techniques and share in turn.

Our first steps:

- Create a waterproof “Green Box” (Thank you Goetz Composites!!!) that could be mounted on deck.

- Use a clear polycarbonate lid with a simple solar powered ventilation fan

- The location and construction of the box should be chosen so as to minimize salt-water intrusion

- For operation in the tropics, a shade cloth will be necessary to reduce temperatures inside the box

As we learned to hard way, there is a very fine line between a ventilated hydroponic system and a non-ventilated solar oven.

In order to maximize agricultural output, we fabricated a germination/rooting box out of a shallow plastic bin to provide a cool, moist, place for the seeds to root before placement in direct sunlight.

At first, the game plan was to place dry seeds on piece of saturated burlap to start the germination process. However, it was soon discovered that with the pitching moment of the boat, we could not keep the seeds from rolling off the mat. Therefore, we began to sprout the seeds with a traditional sprouting process in the hopes that the irregular shape of a germinated seed would reduce the propensity to roll. For the initial germination, a commercially available “sprouting jar” or a water bottle with a screened lid to facilitate daily flushing will suffice.

Lessons learned the hard way:

- Seeds are very difficult to clean out of the nooks and crannies of the bilge, they truly do get everywhere when spilled.

- The logical place to complete the daily flushing of the sprouting jar is the aft pulpit, keep a firm grip on the sprouting jar as a wayward wave could wash the whole experiment away, thus setting you back days.

Once the seeds have started to germinate and the tap roots are showing, they can be spread like paste upon a saturated mat in the rooting box. Although many different growing mediums are possible, sailors may prefer burlap due to its widespread availability and pack-ability. After 2 days in the rooting box, the seeds will set roots into the burlap and sent shoots skyward in search of light. This is the point when the mat should be placed in the box on deck, preferably in the evening when the temps are cooler.

It is important to ensure that the Green Box stays properly ventilated to control temperatures and that the growth medium stays saturated. While we chose manual watering, a simple automated (Arduino) watering system would not be difficult to fabricate for the technically inclined.

While any number of crops could be grown with this method, micro greens are promising due to their inherent nutritional value, short growth time, and ability to store a lot of seeds in a small package. We experimented with clover, broccoli, and arugula in various mix ratios. Pea shoots would also be a good cultivar. With a little practice, an ocean going farmer should be able to produce 1/3 lb of fresh greens per square foot of Green Box per week.